Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (After Gauguin). By Yuki Kihara. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (After Gauguin). By Yuki Kihara. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

An Unstoppable Creative Force

“I make sure that within my own practice that I know, does it touch the mind? And does it touch the heart? Because I want both things to connect. Because it’s really important for me as a Pacific Islander, particularly when I prioritize the Pacific community as the main audience, that we both tantalize the mind and the heart. And that’s how I’ve always made art, that’s how I always want the audience to engage with my work. I feel that it’s a Pacific way of making, which is very political. This is my strategy.”

This year’s Aotearoa New Zealand’s representative at the Venice Biennale is one who leads the charge with firsts – the first person of Pacific descent, the first Fa‘afafine, the first without formal art-school training. Yuki Kihara is a globally celebrated interdisciplinary artist of Japanese and Sāmoan descent who has built a reputation for work that pushes boundaries and is deeply immersed in the critical issues of our time.

Yuki Kihara. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara. Photo: Luke Walker

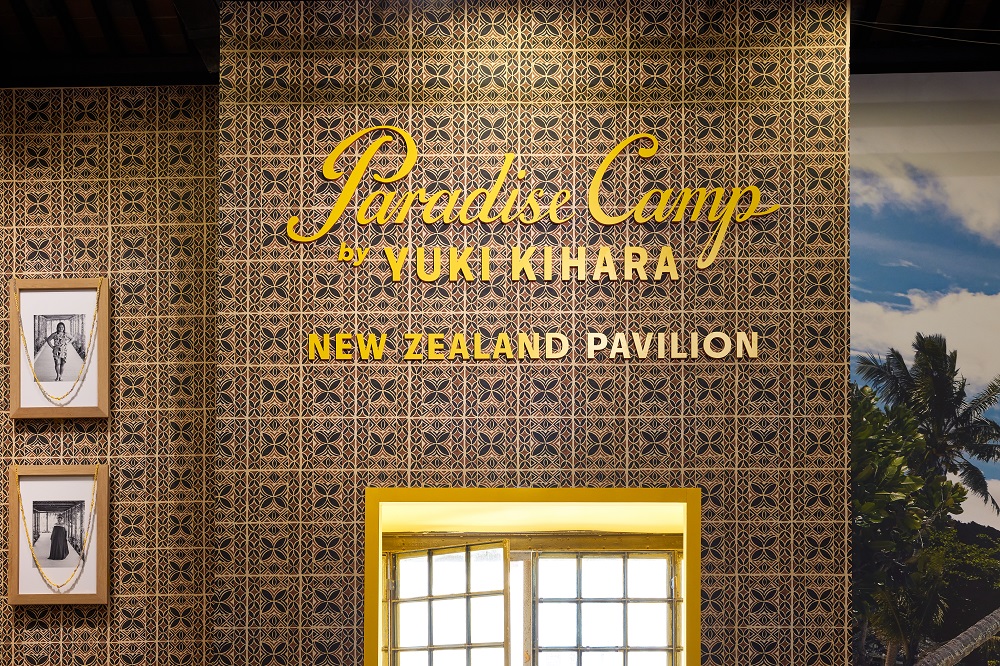

Yuki’s show, Paradise Camp, is curated by Natalie King, who previously curated artist Tracey Moffatt’s exhibition for the Australian Pavilion at the Biennale in 2017. Shot on location on Upolu Island, Sāmoa, Yuki’s work features a local cast and crew of over eighty people. Yuki worked closely with the Fa‘afafine community to produce an engaging project that draws on issues such as climate change and colonization that impact her community.

From the outset, Yuki’s journey has been one of challenging the status quo and living with conviction. Arriving in Wellington in the late ’80s from Sāmoa, Yuki attended boarding school and later majored in fashion at Wellington Polytechnic, which merged with Massey University in 1999. Originally aiming for art school, she settled on fashion as a family compromise. The desire to create in an artistic way, though, had a strong pull.

“I knew that I wanted to do something big – I had ambition. When I was at fashion school, I was making garments that were so ambitious, I didn’t even know how to make them – but I saw it clearly in my mind. And I’ve always been ambitious, because I wanted to challenge myself, to see if I’ve got it in me to do it.”

At the core of this, Yuki says, is because “I wanted to evolve as a person, I wanted to evolve my creativity intellectually, spiritually. I knew that, particularly, as a migrant in Aotearoa, we all have ambitious plans when we migrate to a new country.”

“I didn’t go into fashion school thinking that I was going into a trade, because I was very much treating fashion school like an art school where I was using fabric as a structural material.” The influences include some notable names such as Yohji Yamamoto, John Galliano, and Vivienne Westwood. It was their sculptural sensibilities that inspired Yuki.

This sculptural use of fabrics also has echoes in Yuki’s Pacific heritage. “To me, it was very similar to how Sāmoans, and people in the Pacific also, use textiles as part of their regalia and ceremony – we wrap ourselves with fine mats and tapa cloth – they are very sculptural.”

For Yuki, it’s the specificity that the audiences are attracted to – that when things start to become too generic, the impact is lost. Her work navigates between a moana-centric vision and one that is globalized. A good example is her series サ-モアのうた (Sāmoa no uta) A Song About Sāmoa [2019–2023], which showed two distinctive artforms: Sāmoan siapo (barkcloth) and Japanese kimono. In the show, five kimono were fashioned from siapo – an expression of Yuki’s Japanese-Sāmoan experience. The exhibition, held at Pātaka Art + Museum in Porirua, was symbolic for Yuki. “I said to myself, this is kind of like coming full circle, because Wellington is where I studied fashion. If I had gone to art school, maybe I would have made something totally different.”

サ-モアのうた (Sāmoa no uta) A Song About Sāmoa [2019–2023]

サ-モアのうた (Sāmoa no uta) A Song About Sāmoa [2019–2023]

The lecturers at fashion school had a big impact. “They really pushed me to go 150% with my imagination.” Yuki shares, “My time at fashion school really planted the seed for me to look outside of the industry and to have more concern with more social and political consciousness.”

Throughout Yuki’s twenty-year career, everything she has done has been embedded in identity, politics, and representation. These are timely and important topics about who we are, how we situate ourselves in relation to the world, the community in which we live in, and our rights and responsibilities. Yuki affirms that one aspect of her practice is a socially engaged practice. “This means that I create work in collaboration with diverse communities, and then, in particular, marginalized communities – so that I can be a catalyst to their cause and their plight.”

One of the communities with whom Yuki has worked is the Fa‘afafine community. She produced Wellington’s first Fa‘afafine beauty pageant in 1996. The motivation came from a place of Yuki wanting to use her skills to empower. “I could use my enthusiasm, and some of my administrative and curatorial skills, in providing a platform for voices to come through – being part of the critical discourse in Aotearoa.”

In 2021, Yuki was a catalyst in bringing members of the Sāmoa Fa‘afafine Association (SFA) and the Pacific Climate Change Centre (PCCC) in Vailima, Upolu Island together for a climate change talanoa. The workshop was focused on understanding climate change risks, building capacity, and encouraging action on climate change. The considerable impacts of climate change are a common thread in Yuki’s work, such as in earlier haunting photographs in the wake of tsunami and cyclones.

Yuki’s exhibition at the Venice Biennale is one that is decisively for the Fa‘afafine community. Its production has been on a large scale, with scores of participants, site visits to locations, and an extended pre-production period. Lockdown, Yuki says, “was a blessing in disguise”. The time was used to work on the accompanying comprehensive book, which provides context for the audience about where Yuki’s practice comes from.

Because the show is so complex, detail about it is being drip fed over time. “I’m looking at the intersectionality between identity politics, decolonization, and environmental crisis – it’s a very, very nuanced space. I think that it’s best that people are taken through a journey of the universe.”

Yuki’s push for social change is an integral part of the show – even beyond the art itself. Stipulations mean being able to open dialogue and make change. When galleries express interest in the show, Yuki asks, “Does your institution have gender-neutral bathrooms?” When they ask Yuki why, she tells them, “Paradise Camp prioritizes the Fa‘afafine, Fa‘afatama, gender non-binary, gender nonconforming people.” Yuki emphasizes mechanisms should be in place to look after the audience.

At the core of Yuki’s practice is a decisive commitment to, she says, “your integrity. What are your core principles? What are your core beliefs? It’s important to stick to my guns to what I feel that is important for me, and not just for me – for the community that I represent, and subsequent communities in the future.”

With Paradise Camp now out in the world, Yuki has a thoughtful perspective. “I make the art, and I present it to the world. Now, the artwork has to defend itself. Now, Paradise Camp has a mind of its own, has a wairua of its own that now needs to defend itself, from the critics, the reviews, audience reaction, social media. I’ve made Paradise Camp to be very resilient. It carries its own mana and its own life.”

And for Yuki? “I feel like I’m in this really unique position to create work that furthers the conversation.”

You can enjoy and explore Paradise Camp from the comfort of your home using Virtual Explore. Dive into the immersive at-home digital experience to access footage of Kihara speaking to her research and creation process, and Paradise Camp themes and stories.

https://www.nzatvenice.com/virtual-explore

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara and Natalie King

Yuki Kihara and Natalie King

The Wizard (After Gauguin), 2020. By Yuki Kihara. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

The Wizard (After Gauguin), 2020. By Yuki Kihara. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara’s Vārchive. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara’s Vārchive. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara’s Vārchive. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker

Yuki Kihara’s Vārchive. Installation view, Biennale Arte 2022. Photo: Luke Walker