Dr Roger Ball with the decorated bodhrán (Irish drum) he received in recognition of his scientific contribution

Dr Roger Ball with the decorated bodhrán (Irish drum) he received in recognition of his scientific contribution

From soil to science: a Massey pioneer’s legacy in agricultural science

At 85 years old, Dr Roger Ball reflects on a career that helped shape the foundations of modern agricultural science in Aotearoa New Zealand. His story is one of scientific accomplishment and of humility, deep curiosity, and a steadfast belief in the power of education, community, and the land.

Massey in the 1950s: a formative time

Born in Masterton and raised in a semi-rural environment, Roger’s early experiences on farms from the age of 14 set the stage for a lifetime connection to agriculture. “I grew up a ‘towny’, but working on farms and joining the Young Farmers’ Club opened up my world,” he says. That world expanded further when he was awarded a Rural Field Cadetship, which steered him to Massey Agricultural College.

Roger enrolled at Massey in the late 1950s, when the college was much smaller than the modern university. The student experience was personal, close-knit, and sometimes a little wild. “It was similar to a boarding school. The intake of degree students was around 70, and social life in the hostels could be quite chaotic – water fights, pranks, and a real sense of camaraderie,” Roger remembers.

He thrived in both the classroom and the field. A scholarship from the Farmers’ Union enabled him to complete a master’s in Soil Science under the guidance of the late Dr Cliff Fife, graduating with First Class Honours. His fascination with soil fertility and plant nutrition laid the foundation for a career that would challenge long-held assumptions and reshape farming practices nationwide.

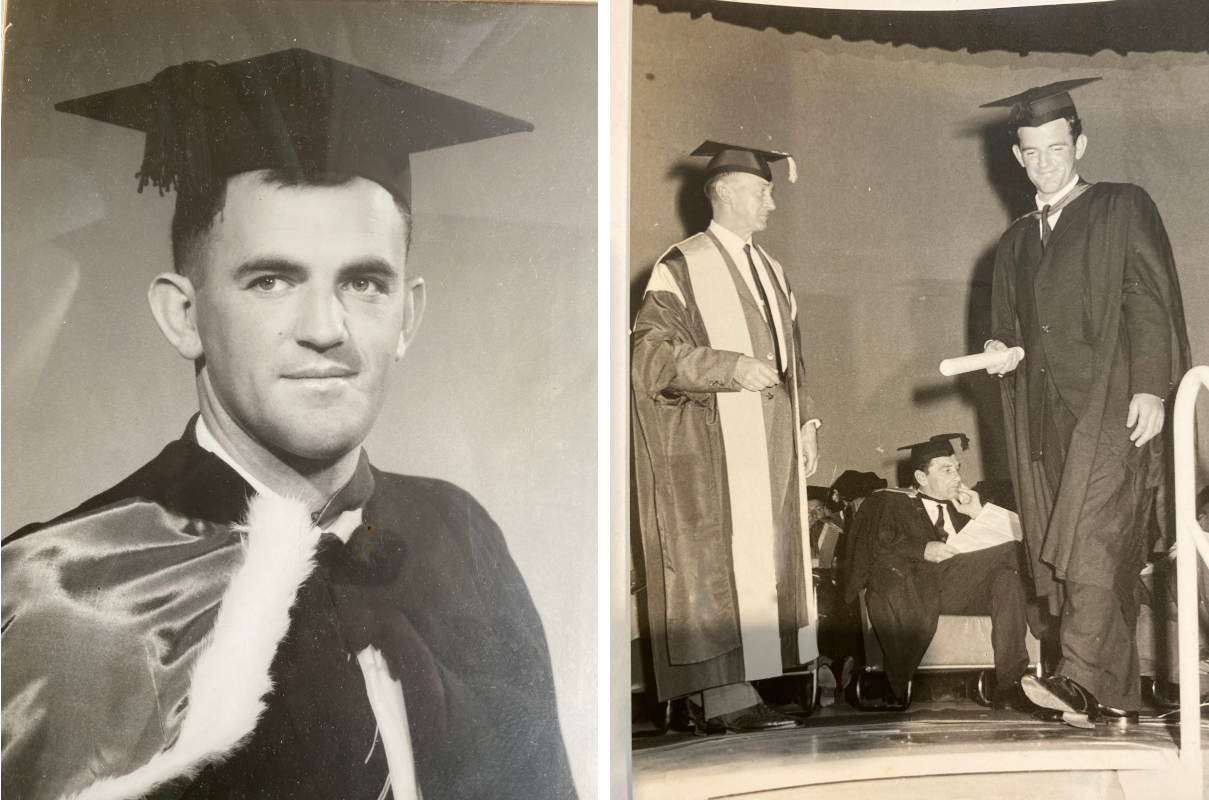

Left: Bachelor of Agricultural Science 1964. Right: Master of Agricultural Science 1967 presented by Alan Weir, Registrar

Left: Bachelor of Agricultural Science 1964. Right: Master of Agricultural Science 1967 presented by Alan Weir, Registrar

Becoming “Mr Nitrogen”

Roger started his career as a research scientist at the Grasslands Division of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), where he pursued research around the dynamics of nitrogen (N) in pastoral agriculture: inputs, transformations, outputs and losses. At the time, the dominant belief in New Zealand was that fertiliser nitrogen had no place in grassland farming. Roger’s experimental work slowly but surely shifted that thinking.

“There were strong views against using nitrogen,” he explains. “The concern was that it would boost grasses and damage clover, upsetting the balance. But our research showed that, under the right conditions, there were significant responses to nitrogen application.”

His work gained traction not only through journal publications but also by engaging directly with farmers. Alongside colleagues Dr Tony Field and Phil Theobold, Roger conducted field trials and shared findings at field days and regional events. His dedication to translating science into practice earned him the nickname “Mr Nitrogen” – especially in the lower North Island.

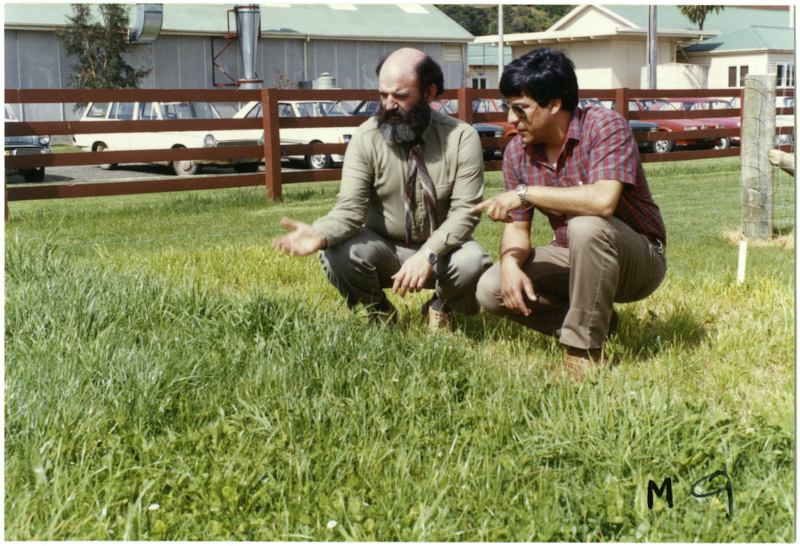

Scientists Emilio Ruz (right) and Roger Ball

Scientists Emilio Ruz (right) and Roger Ball

Taking New Zealand science to the world

Roger completed a PhD degree in 1979, by which time Massey attained its present status as a university. The work was supervised by the late Professor Bram (Watty) Watkin in the Agronomy Department. Roger focused again on the dynamics of nitrogen, especially the leaching losses of nitrate from grazed pasture. That same year, an unexpected opportunity presented: a travel scholarship from the National Research Advisory Council. The offer was open-ended – “Where to?” he asked. “Anywhere,” they said. “For how long?” “As long as you like, up to three years.”

With the support of his director, Roger, his wife Oline, and their two teenage sons, Harley and Garth, embarked on an academic and family adventure to England and Ireland. In Berkshire, he collaborated with the late Dr John C. Ryden (another Massey PhD graduate), producing a landmark study on nitrate leaching under sheep-grazed pastures. Their findings were published in Nature – one of the proudest achievements of Roger’s career.

“I am most proud of acceptance for publication by Nature of our study into leaching of nitrate below pasture grazed by sheep,” Roger reflects. “My PhD had focused on the dynamics of nitrogen in grass-clover swards, either cut or grazed by sheep. I developed a method for identifying and quantifying nitrate leaching below pastures. A few years later, in England, I worked with John, and together we used this methodology to produce the report deemed worthy of publication.”

That publication in Nature remains one of Roger’s proudest achievements, not just for its scientific merit but for what it represented — decades of dedication to understanding the real-world complexities of pastoral systems. “My career also made its major contribution to agricultural science because I incorporated grazing animals into the management of experimental grasslands, replacing the widely-used mowers,” he says. “I have an enduring sense of pride about having changed the direction of understanding in pastoral agriculture — or at least contributed to that.”

Their next stop was Ireland, where the family lived on the top floor of Johnstown Castle – a majestic but chilly residence that doubled as a research centre. Roger worked with Dr Pat Murphy and the late Dessie Allen on nitrogen cycling in clover-based pastures. Before leaving, the staff hosted a farewell ceilidh and presented Roger with a decorated bodhrán (Irish drum) in recognition of his scientific contribution and quest for Irish culture and history.

The bodhrán returns to Johnstown Castle after 40 years. Presenting it is Ms Pauline O'Donoghue, to Matt Wheeler representing the Museum. Also present : ( L to R ) Dr. Bill Kelly (Paulines partner); Dr Noel Culleton, Director; Dr Aidan Conway (now 90 years) who was Head of the Research Centre when Ball worked with them, and Dr Owen Carton, a colleague and friend, who has visited Palmerston North.

The bodhrán returns to Johnstown Castle after 40 years. Presenting it is Ms Pauline O'Donoghue, to Matt Wheeler representing the Museum. Also present : ( L to R ) Dr. Bill Kelly (Paulines partner); Dr Noel Culleton, Director; Dr Aidan Conway (now 90 years) who was Head of the Research Centre when Ball worked with them, and Dr Owen Carton, a colleague and friend, who has visited Palmerston North.

A legacy of learning

Returning to New Zealand, Roger resumed his work at DSIR and continued co-supervising postgraduate students and mentoring young scientists. But the landscape of science was changing. Resources were shifting, and the focus on long-term, curiosity-driven research was giving way to more commercially oriented agendas.

Still, Roger remained active in the field. In 1991, he was awarded the Geoffrey Peren Medal – a rare honour recognising his outstanding contribution to agricultural science and the Massey community. “I felt nervous and privileged,” he recalls. “No one was more delighted than my elderly mother – a woman of doughty Irish heritage who firmly believed in the power of education. She was there for the ceremony. It was a very special moment.”

In 1992, Roger took early retirement from DSIR and returned to hands-on farming with a lifestyle block near Masterton, growing grapes and living out a long-held love for the land. “There was a natural attraction for me,” he says. “Farming kept me fit, active, and connected to what really mattered.”

Now retired in Palmerston North with Oline, Roger continues cultivating life in every sense. He maintains an organic garden, plays pétanque, dabbles in philately, and enjoys board games, Rebus Club outings, and church activities. “The spirit of enquiry doesn’t just disappear,” he says. “But the canvas gets smaller.”

He also remains deeply connected to Massey University. Not only did he earn multiple qualifications there, but his wife Oline, daughter Philippa Peck, and two grandsons are also proud Massey graduates.

“Massey is our Alma Mater – our nurturing mother,” Roger says. “We’re very aware of the scholarships and support that helped us along the way. That’s why we continue to support the Massey Foundation.”

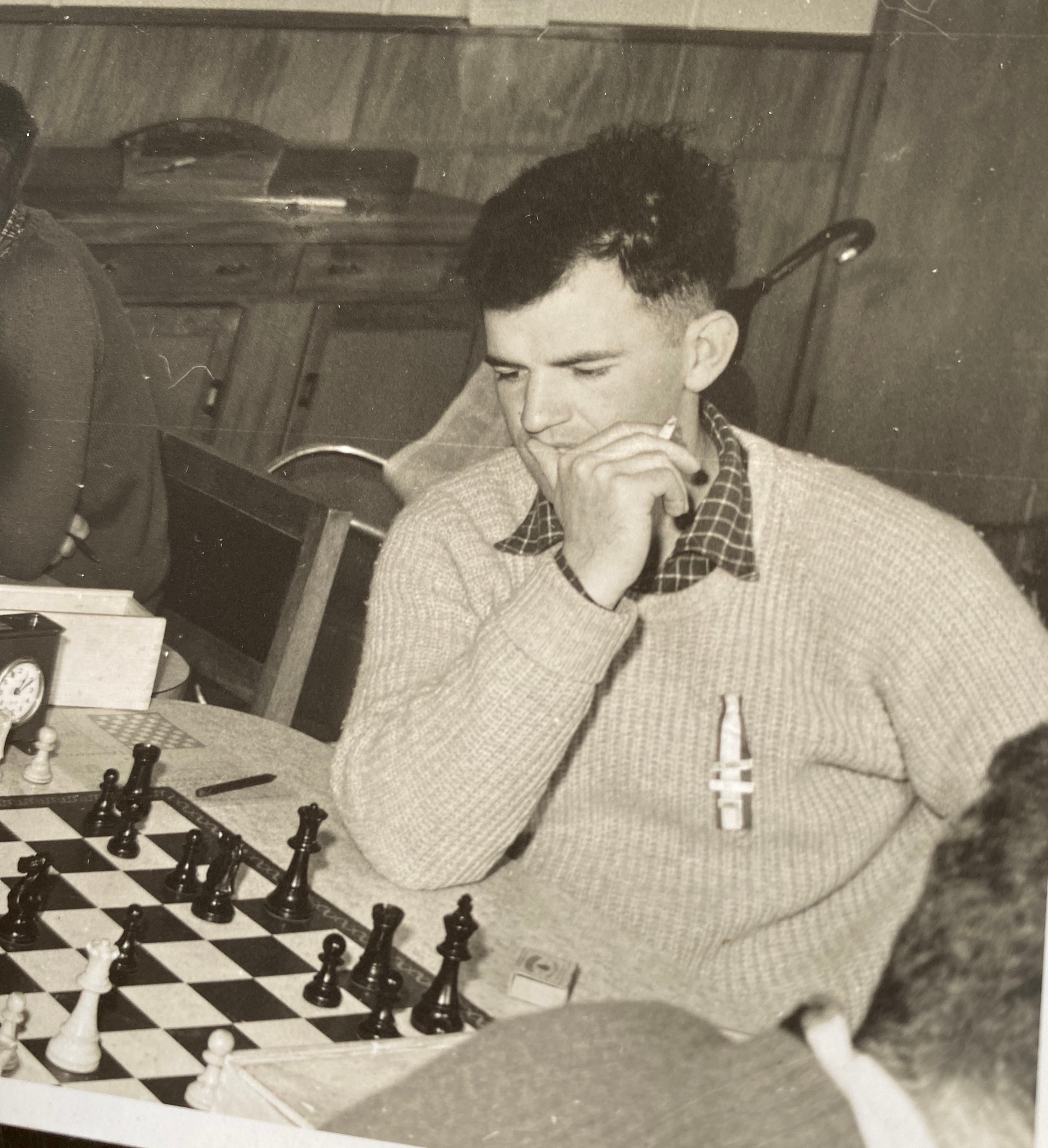

Playing chess for Massey at Winter Tournament early 1960s

Playing chess for Massey at Winter Tournament early 1960s

Advice for the next generation

When asked what guidance he’d offer to young agricultural scientists today, Roger is thoughtful: “I feel I worked in a golden age – where we followed ideas because they were interesting, not just because they fit a funding model. I’d say, build a strong academic foundation and remain open to where your curiosity leads you.”

Roger’s life reminds us that science is not just about data and discoveries – it’s about people, persistence, and the pursuit of knowledge that makes a difference.

Family group at Wharerata. Seated: Oline and Roger; standing, L to R, Garth, Harley and Philippa.

Family group at Wharerata. Seated: Oline and Roger; standing, L to R, Garth, Harley and Philippa.