Joshua Ambler: Designing with purpose at Hutt City Council

The path of Joshua Ambler, Ngāti Korokoro, Ngāpuhi, to design didn’t begin in a studio; it began behind a café counter. He grew up “everywhere,” a result of Māori urban migration, “but Hokianga is home.” After moving between the Far North and Auckland as a kid, he left school early and went straight to work. By 28, he was running five cafés and managing 40 staff.

“I thought that’s what I’d do for the rest of my life,” he says. But after years of back-to-back shifts, he found himself asking a bigger question: Is this really it?

He enrolled in a six-month foundation course in art and design. “What’s the worst that could happen?” he thought, and it “unlocked something.” He’d always been good at art and photography, but the course gave him the confidence to pursue design seriously. Keen to step outside his comfort zone, he left Auckland for Wellington and enrolled in Spatial Design at Massey. Looking back, he says, “It was one of the biggest, most life-changing decisions I’ve made.”

Not Another Dark Alleyway

Not Another Dark Alleyway

Finding his why at Massey

When Joshua arrived at Massey, he described himself as Māori but severely disconnected from his māoritanga. “I had little knowledge of te reo, mātauranga or my whakapapa.” Meeting Māori staff on campus became the start of a deeper journey. “My courses were kind of therapeutic, a way for me to reconnect to my ancestry,” he says.

He began to read widely, taking courses in Te Tiriti, Māori health, and anthropology. He explored the impacts of colonisation across Aotearoa, Australia, and Canada, connecting land dispossession to the breakdown of Indigenous communities and negative health outcomes.

“I finally had my why — why so many Māori, like me, felt culturally disconnected, and how disconnection creates negative statistics for Māori. It was a moment where my study collided with my lived experience. I knew then, I had to do something to change the trend and create better outcomes for my people”

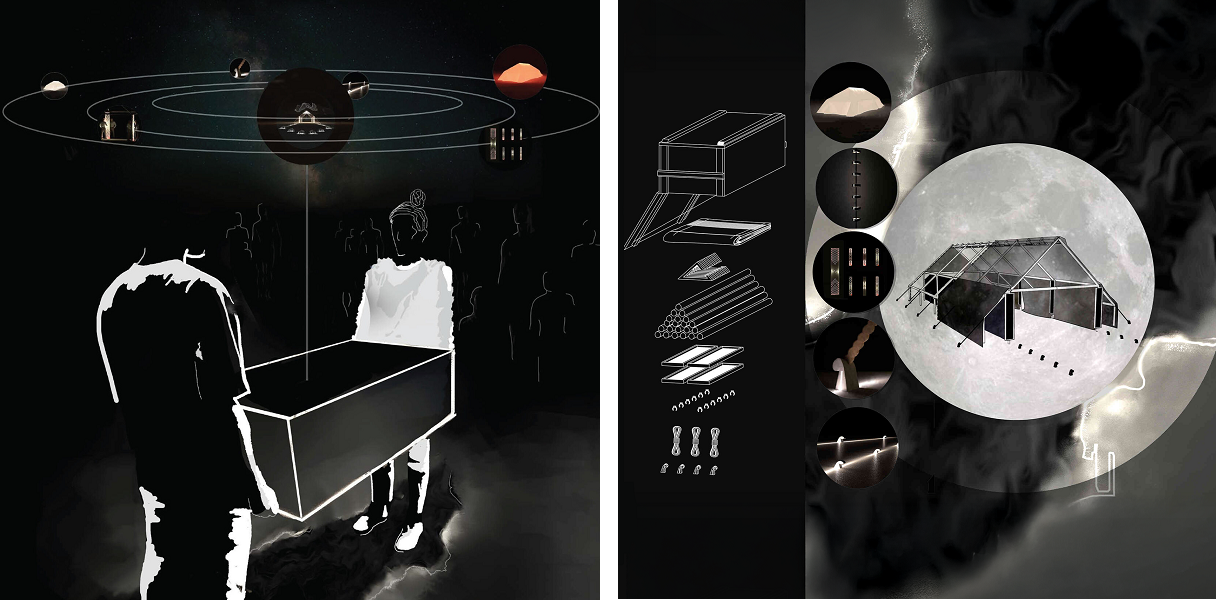

By his fourth year, “Mana Whenua across Aotearoa were engaged in passive resistance, contesting harmful development on culturally significant land” and Joshua knew what that led to for Māori. Joshua framed his capstone project, He Keteparaha, as “a koha to Māori. It was designed to offer physical, mental, and spiritual protection, supporting whānau who were at risk of being fragmented from whenua due to urban development.”

The work foregrounded Mana Whenua authority and the exercise of tino rangatiratanga, asking a practical question: If Mana Whenua communities were to design our cities, what might that look like?

He Keteparaha Mō Te Mau Whenua

He Keteparaha Mō Te Mau Whenua

From studio to city: a role with remit

After a presentation to Hutt City Council, Dr Rebecca Kiddle approached him with an offer to join the organisation. Joshua now serves as Kaupapa Māori Design Officer, working alongside the Urban Design team and Mana Whenua. The kaupapa remains the same, better outcomes for Māori, but now channelled through embedding Mana Whenua aspirations into council operations and urban development.

“When Mana Whenua aspirations are activated in council, the outcomes meet the needs of all people. That’s the beauty of tikanga. I’m beginning to see a positive shift in partnership between local government and Mana Whenua, which is promising,” he says. That shift shows up in how projects are initiated, who is in the room, what success looks like, and how spaces are designed to function for all community members.

Working alongside Mana Whenua, Joshua has led HCC through Tiriti-based urban design, delivering projects framed around three core Mana Whenua aspirations:

- Makaurangi – places that tell kōrero tuku iho (ancestral stories)

- Mānākitanga – places that support the needs of people who use them

- Kaitiakitanga – places that rebalance our relationship with the environment

Pito One Landings / Petone 2040

A highlight of his career is the Pito One Landings initiative, two small but impactful projects centred around culturally significant areas now hemmed in by industrial development.

Pito One Pā Landing

Pito One Pā Landing

Pito One Pā Landing

This project centres around an urupā linked to Te Āti Awa Paramount Chief Honiana Te Puni and the early settlement of Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Over time, industrial development had built up around the urupā, negatively affecting its functionality.

There was no place to gather, no seating, no proper hand-washing area, and tangihanga practices had ceased. “Urupā are a Māori hub archetype, places where Māori reconnect with whakapapa and transmit cultural frameworks to the next generation. But when urupā aren’t functional, it becomes really difficult for whānau to continue intergenerational transmission of Māori ways of being,” Joshua explains.

The design team reclaimed road reserve to create a small gathering space, installed a waharoa (gateway) to support transitions of tapu and noa, upgraded facilities, and added contemporary pou designed to be carved later by local carvers. Crucially, the work is adaptable, allowing Mana Whenua to continue shaping the site over time.

The result is more than a facelift: it has sparked a heritage conservation management plan and fresh kōrero about interring ashes, allowing whānau who pass to “come home.”

Maru Streets for people

Maru Streets for people

Hīkoikoi Landing

Another strand of the Pito One Landings initiative focuses on pā sites. “You wouldn’t know these even existed,” says Joshua. “They’d been erased from the landscape over the last 200 years.”

Mana Whenua voiced a clear aspiration: the city should connect to their history and tell the stories of place. “Research shows that when whānau histories are visible and accessible, they strengthen tūrangawaewae and identity, with positive impacts on wellbeing,” he explains.

The project reveals the area’s history, particularly its role in transporting kaimoana from the coast up the river via waka. Co-designed with Mana Whenua, every aspect of the project’s look and feel was shaped by kōrero tuku iho.

Among the cultural design elements, a standout is the pā kahawai sculpture. “Pā kahawai were traditional lures used to catch kahawai, and the place where the sculpture will eventually stand is still used for fishing today. It feels deeply right for the area.”

What “getting it right” looks like

Joshua’s success metric isn’t a glossy render; it’s a city scene. Whānau gathering kai from green spaces, tamariki and kaumatua swimming in clean rivers, streets that foster dignity, and visitors pausing to interact with Mana Whenua stories.

Although he admits it’s more complex than that, In a time of high living costs, design needs to meet basic needs: access to fresh food, warm homes, and spaces that make daily life easier for those with the least. “Design can actively improve lives and designers have the ability to do that.” But he stresses the need for more designers who think holistically about how we design cities.

For students wanting to create impact, Joshua offers two anchors. First: “Figure out your why. Your why will keep you on track. What about the world bothers you most, and what knowledge or skills do you need to change it? Secondly, “never underestimate the power of care”, as Dr Seuss put it: “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

To Māori students: “you can lead, create, and transform our world. Begin where you are, follow the wairua, and connect with change makers. Kia whakakī tō kete ki te mātauranga - fill your kete with knowledge. Our people wait for you.”