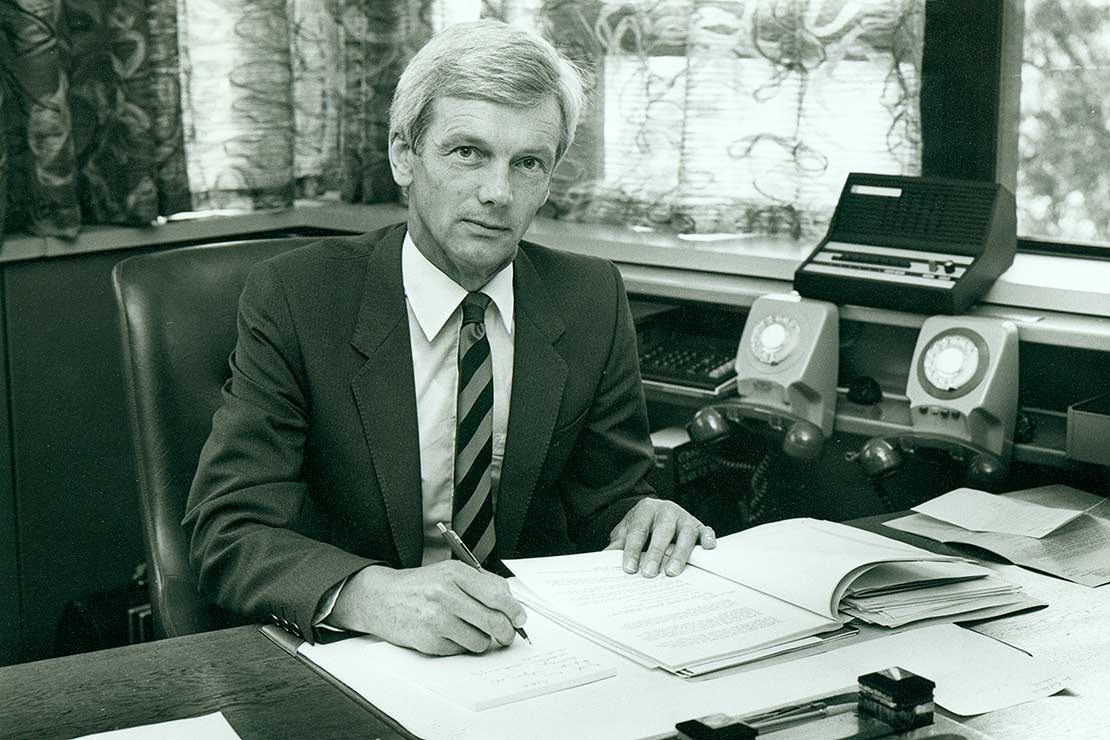

Obituary: Sir Neil Waters MSc, PhD (NZ), DSc (Auck), FNZIC, FRSNZ

By Michael Belgrave

Neil Waters took up the vice-chancellorship of Massey University in 1983. He followed two legendary leaders who had, over 50 years, established Massey as an agricultural college and transformed it into a university. While Geoffrey Peren (principal 1927-58) and Alan Stewart (Principal 1959-63, Vice-Chancellor 1963-82) were much longer at the helm than Waters’ 13 years, he was every bit as important in Massey’s development as a university. Peren had formed the agricultural college, coped with the threats of Depression and World War II, while Stewart had built a university (at times literally) from its warring parts to provide for what seemed like an ever-increasing flood of students. Waters’ period as Vice-Chancellor corresponded with the dramatic reforms of finance ministers Roger Douglas and Ruth Richardson, which turned all areas of government policy on their end, including that of tertiary education. Waters had no sympathy with the Labour Government’s Reform agenda, but he took the opportunity it provided to transform Massey from its Palmerston North base to become a national university.

Born Thomas Neil Morris Waters in New Plymouth on April 10, 1931, he was the son of Edwin Benjamin Waters and Kathleen Emily (nee Morris. He attended Awakino Primary School, New Plymouth Boys’ High, Auckland University College, from where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in 1953 and a Master of Science (Chemistry) in 1954. He completed his doctorate in 1958 and a Doctor of Science in 1969. Both Waters and his wife Joyce Mary Partridge, whom he married in 1959, were working in Auckland’s crystallography unit as postgraduate students. Two years in England followed, with a fellowship at the Atomic Energy Authority. In 1961 he returned to the University of Auckland to take up lectureship in chemistry. In 1970 he was appointed to a personal chair. He was conferred with an Honorary Doctor of Science by the University of East Asia in 1986 and by Massey University in 1996. He was knighted for his services to education in 1995. In 2011 he received the Sir Geoffrey Peren Distinguished Alumni Award.

Waters was a man of reserved dignity, self-effacing, reticent but with a wry sense of humour. He promoted discussion and debate without intervention and was ever polite in his dealings with everyone. This included government ministers and officials, despite his often deep seated concern about the impact of their policies on universities and their treatment of Massey. His briefings of staff were devoid of the razzmatazz of branding and accentuating the positive. Punctuated with the threats Massey faced, he shared his views as with colleagues in ways that were inclusive and, in the end, inspirational. Beneath this reticence were a set of core values; a belief in the dignity of the individual, in the humanising potential of the university and in the future of New Zealand. This reticence also disguised the courage and determination to hold on to what he considered important and to push through with proposals he thought essential, despite often determined opposition.

He was far from the approved choice of his predecessor. The University Grants Committee, which appointed him, was looking for someone with very different skills from the autocratic and micro-managing Stewart. Waters believed in a university run by its departments, reflecting the enthusiasms, aspirations and potential of its disciplines. Heads of department initially had direct access to him as Vice-Chancellor. With 50 academic departments, this was far from streamlined and did not last and was replaced by a leadership group, but it represented an appreciated commitment to consultation in an academic-led university. His selection of Graeme Fraser and Ian Watson to manage the academic and research life of the university was part of the strategy.

Waters was appointed in the dying and fractious years of Robert Muldoon’s National Government. Political and ideological conflict was breaking down a post-war consensus in the role of universities as guides to the future. Universities and their staff came under increasing attack for being too left-wing or too right-wing, too representative of privilege or speaking too loudly for the underdog. In all of this, Waters strongly defended academic freedom and supported academics and disciplines who increasingly came into conflict with government. He also supported applied disciplines, such as nursing, education and social work, which were reassessing their relationships with iwi, with the professions they supported and with their clients. Waters strongly supported the increasing role of Māori as tangata whenua within the university and the work of Professor of Māori Studies Mason Durie. For many at Massey these challenges were both disturbing and exciting.

Times were changing and not in ways that Waters welcomed. The election of David Lange’s 1984 Labour Government ushered in a new age of market-driven reform. Waters preferred to deal with National rather than Labour governments, which highlighted his antipathy to Labour’s radical reforms to tertiary education. Labour’s faith in market competition to determine educational policy threatened not only everything that Waters considered important in Massey’s commitment to teaching and research, in his view, it undermined New Zealand strategically. Agriculture, the centrepiece of Massey’s programmes, was severely threatened by Labour’s withdrawal of subsidies and commercialisation of government activities in rural communities. Waters fought to preserve the country’s commitment to research and teaching on agriculture and food technology, when dramatic declines in numbers threatened these programmes’ viability.

Not only did Waters fear that the Government’s reforms would undermine the independence of the country’s universities, leaving them at the whim of short-term ministerial enthusiasms, he was at odds with the Government’s determination to reform the way that universities operated. He treated with scorn the hierarchical managerialism so beloved of the reformers. He dismissed strategic plans as “the refuge of busybodies or the unimaginative who spend great amounts of time on the details feeling that they are directing the future but failing to notice that it is gone elsewhere”.

A conservative, Waters sought to preserve the very best traditions of university enquiry and collegiality from the threats posed by the Labour Government’s reform of tertiary education. Taking Massey to Albany, Auckland, was not an expression of confidence in the government’s agenda, but primarily designed to preserve Massey’s independence. The decision to go to Albany in 1989 would transform Massey, make the university a national university, and emphasised its place in the Pacific Rim. Waters’ initial aspiration to use the new campus to be self-supporting by attracting overseas investment and overseas students was never realised, but the development occurred at a time when unemployment was increasing the demand for tertiary education. It was built and the students came. Waters drew on a well-established commitment within the university to work with other educational providers, looking outward from the Manawatū to Asia and the Pacific. But he never had the full support of the Massey University Council, and many in Palmerston North feared the impact on their own campus and city. The superb campus only occurred through Waters’ vision and drive and will be his memorial.

Neil Waters supported debate, defended academic freedom, not as a privilege, but as fundamental to New Zealand’s economic, social and cultural future. His final message to the University was typical of his values and his aspirations:

Through all the continuing turmoil and change, the University must hold fast to the eternal virtues of its mission, to its commitment to excellence, the pursuit of truth, the free exchange of ideas, the pursuit of knowledge and its obligations to the future.

He died on June 7, aged 87, and is survived by Professor Emeritus Lady Joyce Waters.

Michael Belgrave is a Professor of History at Massey University who has published widely on Treaty of Waitangi and Māori issues and is author of From Empire’s Servant to Global Citizen, the history of Massey University published in 2016.

Sir Neil at work in 1983