Hazel Riseborough

Hazel Riseborough’s singular working life took her from the woolsheds of Wairarapa to researching for the Waitangi Tribunal. The first woman to qualify through Massey as a wool classer, she later became a pioneering historian and successful author. Bevan Rapson meets a remarkable woman whose links with Massey reach back half a century.

Hazel Riseborough’s singular working life took her from the woolsheds of Wairarapa to researching for the Waitangi Tribunal. The first woman to qualify through Massey as a wool classer, she later became a pioneering historian and successful author. Bevan Rapson meets a remarkable woman whose links with Massey reach back half a century.

Never mind the dairy boom, Hazel Riseborough still prefers sheep country.

The former wool classer turned historian and author criss-crossed the country researching her latest book and was dismayed at the rise of dairying in places like Central Otago, where she found shearing sheds falling down and cows on the fields where sheep once grazed. “Shocking,” she says. “I don’t care for cow country.”

Happily, a recent bus trip from the central North Island down to Massey University – which she first attended in 1949 when it was Massey Agricultural College – took her through classic sheep territory. “I suddenly felt comfortable.”

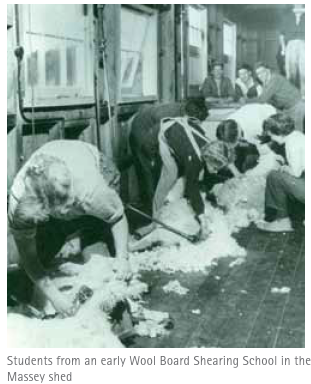

Her preference is easily explained: Riseborough’s links to sheep and wool date back to those early days at Massey when she was the first female – ‘girl’ was standard usage in those days – to qualify with a diploma in wool and wool classing, then continued through research work with wool at Massey in the 1960s and came full circle with her book Shear Hard Work: A History of New Zealand Shearing, published last year by Auckland University Press.

Just those details suggest a remarkable journey, but Riseborough also fitted in careers as an Italian interpreter and as a highly regarded historian and researcher specialising in 19th-century relations between Māori and Pakeha.

She still has publishers wanting her to take on further books, but during a long conversation in a friend’s Rotorua living room sternly dismisses the idea that she should write a memoir of her life: “Nobody needs a book about me”.

Even growing up in suburban Wellington in the 1930s and ’40s, Riseborough was drawn to the countryside. Raised by English-born parents in a part of Wadestown now known as Wilton, she and her brother could climb through Wilton Bush and out into sheep country. “If we went the other way there was a dairy farm where they milked by hand.”

The glimpses of a semi-rural life whetted her appetite and she set her heart on studying at Massey Agricultural College.

After attending Wellington Girls’ College, then doing a stint of practical experience on a farm in Wairarapa she became one of only three girls on Massey’s Diploma in Agriculture course. “One dropped out very soon, and the other one and I went right through, and I was determined I was going on to do the wool course after that.”

After attending Wellington Girls’ College, then doing a stint of practical experience on a farm in Wairarapa she became one of only three girls on Massey’s Diploma in Agriculture course. “One dropped out very soon, and the other one and I went right through, and I was determined I was going on to do the wool course after that.”

The general sheep course had included a grounding in wool. “That was the part that intrigued me most. They said no girl had ever completed the wool course, and I said, ‘Well I’m going to,’ and I did.”

At that time – 1951 – there was no particular feminist sensibility attached to her ambitions. “If I wanted to do it I got on and did it,” she says.

She was the first woman to qualify as a classer through Massey, but emphasises that Māori women were classing years earlier on the East Coast; “brilliant classers”, but without formal qualifications.

Riseborough’s working life began with classing in sheds on the Wairarapa coast, with Māori shearing gangs. The working environment was “whanau-oriented”, she recalls. “Mum, Dad and the kids might be there, and the littlies were looked after by the cook.”

After a few years she headed off for her first stint overseas, with farm work in Britain and a hitchhiking tour of western Europe before returning to Massey, where she began work as a technician in the Sheep Husbandry Department. She was assigned to help the pioneering Dr Francis Dry, developer of the Drysdale breed, and has vivid memories of working with him and his flocks of “these great hairy monsters”: big sheep with horns. “I’d have to catch this great big Drysdale ram, hold it by the horns and read its ear tag number. He’s on the other side of the pen with his little notebook. Then he’d start, ‘Oh, I knew this ram’s grandmother…’ and while he told me about it he would lose his place in the notebook, and I’d have to catch the ram again.”

By 1960, Riseborough was ready for more overseas adventures, heading for Italy where the Olympic Games were held that year. She learned the language at the Italian University for Foreigners in Perugia, then worked as an interpreter at

the medical school then at a scientific institute in Rome. She liked Italy enough to live there for about five years – travelling in the summers – but life there in the 1960s had its challenges. “Italian males were the main drawback,” she recalls. “You pretty well had to have a man along to repel the others.”

Once again she returned to Massey, this time landing a job as a research assistant analysing wool blends for carpet and blanket manufacturers with the help of the institution’s first computer.

Riseborough’s Italian opened another opportunity. An Italian firm was building the Tongariro power scheme and needed an interpreter. The money was better than at Massey, and with a house supplied. “So I said to them at Massey, ‘Sorry boys but I’m off’.” Her work ranged from producing an Italian version of the local road code to taking Italian workers and their families to the doctor. “Each day I morphed from being a New Zealand girl at home to being an Italian girl in the office.

After another overseas sojourn took her to Western Australia, she eventually returned to the central North Island where she began to develop a long-held interest in the Māori language.

At high school, Riseborough already had been drawn towards the Māori pupils in her classes and had made her first attempts at learning Māori. “There was no reasoning about it then, but later, trying to analyse what had sent me in

At high school, Riseborough already had been drawn towards the Māori pupils in her classes and had made her first attempts at learning Māori. “There was no reasoning about it then, but later, trying to analyse what had sent me in

that direction, I think I felt that to be a real New Zealander I had to be much more aware of the Māori world.”

Back from Australia, she started by recording Māori lessons on the radio and in 1974 enrolled again at Massey for extramural Māori studies papers. By 1978, having passed all of the Māori papers then available extramurally – and branched into history along the way – she moved back to Massey to continue her studies, landing a job as a clerk while she completed a degree in Māori studies, and won a scholarship to do honours.

Her honour’s thesis An Italian View of the 19th Century Māori World drew on her translations from books written by two Italian priests who came to New Zealand in the 1860s and 1880s.

That thesis won her a scholarship to embark on a doctorate. She chose a PhD topic that covered the invasion of Parihaka in Taranaki by government troops and volunteers. In 1981 Riseborough had been to the centenary of the event and felt the grievance of Taranaki as though it was something that had just happened. “It was so real and so alive. I thought to myself, what on earth did the government do to these people up here that left this grievance?”

She dug deeply into the government documents. Telegram communications between government ministers proved a goldmine of information. “They were so sure of the rightness of what they were doing that they kept all the documents.” Her highly-regarded thesis was eventually published in 1989 as Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878 to 1884.

In the midst of the Māori ‘renaissance’ of the 1980s, Riseborough found herself involved in Massey’s establishment of a stand-alone Māori Department. While the department awaited the arrival of a new head, Mason Durie, she looked

after its administrative affairs. Personally, she faced resentment from some in the department – “some of the students were very prejudiced about this Pa-keha- female” – but she remained philosophical about the snubs. “I understood where they were coming from, they’d been discriminated against for years and years. Who was I to complain, as a Pa-keha-, about Māori looking at things from the other end of the telescope?”

She remembers a turning point when Durie asked her to accompany him to a funeral. “Well it was as though he’d thrown his cloak over me;"

Article date: 18/2/2021